By Chris Herring

This is the third article in a series covering the criminalization of homelessness in San Francisco, drawing from findings of the Coalition’s recently released report Punishing the Poorest, which can be downloaded here.

San Francisco has more anti-homeless laws than any other city in California—23 ordinances banning sitting, sleeping, standing, and begging in public places. Political disputes over these laws are well known. But what often goes overlooked are the consequences of such laws on homeless persons.

To understand the impact of San Francisco’s punitive approach to managing homelessness, the Coalition on Homelessness (also publisher of the Street Sheet) surveyed 351 homeless people about their experiences with criminalization under the supervision of researchers from the University of California at Berkeley Law School’s Human Rights Center.

The study found that 69% of respondents received a citation in the past year. Most received more than one citation, and 22% received over five citations in the past year. These findings are in line with a 2012 survey carried out by the Western Regional Advocacy Project (WRAP), which found that 63% of homeless people had been cited for sleeping, 56% for sitting or lying down, and 52% for loitering or hanging out during their current episode of homeless people.

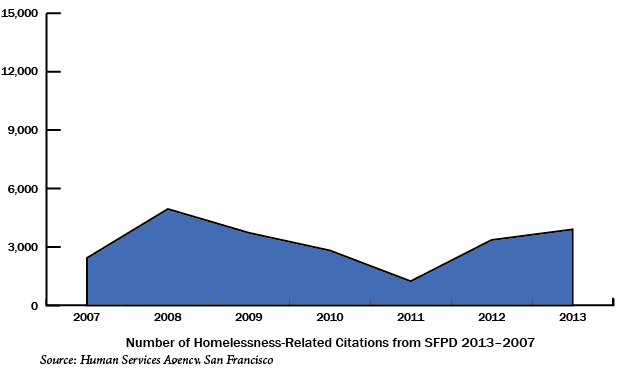

The high frequency of ticketing reported in our survey also aligns with data we received from City agencies through a series of Freedom of Information Act Requests. On average, nearly 100 citations are given out each week for activities associated with homelessness in San Francisco.

Ticketing for violation of anti-homeless laws is on the rise. Since 2011, the SFPD has nearly tripled the number of citations issued for sleeping, sitting, and begging from issuing 1,231 tickets in 2011 to 3,350 in 2013. An even more dramatic punitive push is seen with San Francisco’s Parks where citations for camping and sleeping exploded six times over from 165 citations in 2011 to 963 in 2014.

Process as Punishment: The Irrelevance of Resolving Fines

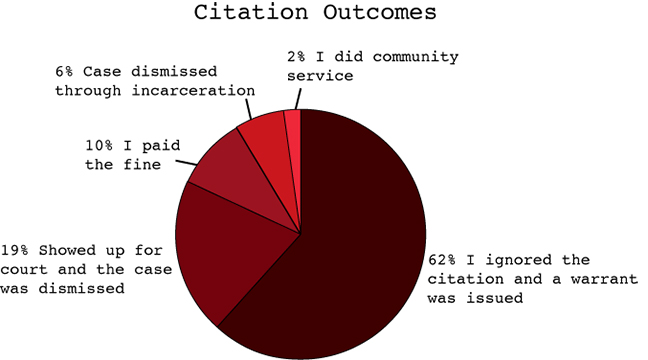

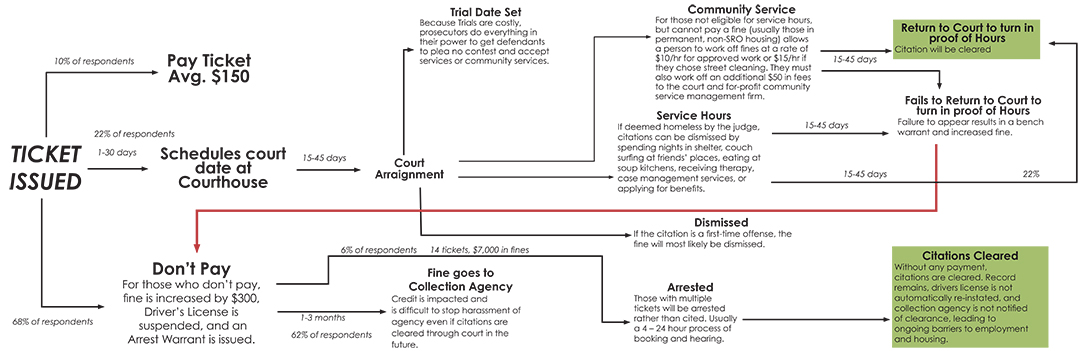

What happens to the thousands of citations handed to the city’s homeless people each year? Our study found that only 10% of respondents handled their most recent citation in the way citations are normally resolved by housed people—through payment. The remaining 90% of respondents confronted a maze of bureaucratic processes and additional penalties that perpetuate rather than alleviate the homeless condition at which they are aimed.

Following the flow chart below, we see three general paths to resolving a citation. The path least travelled is paying the fine, which averages around $150—a path that was taken by only 10% of respondents in the case of their most recent citation.

The second path, which 21% of respondents took, was to resolve their fine through the time-consuming and often confusing alternatives of documenting hours spent receiving social services or doing community service. For a significant number of survey respondents (19%), their most recent citation was dismissed either because it was a first offense, or, more likely, because they documented their interactions with homeless service providers. To take this route, the offender must first go to the courthouse at 850 Bryant and schedule a court date, attend arraignment, and attend another court date to present a signed form documenting the hours of services received. Without being offered any additional support that improves their plight, the homeless “offender” has been rolled through a time-consuming and costly procedure, for both herself and the court. As Z, a 22-year-old African American woman who described her experience with this process explained, “Technically, it made me feel like I was a piece on somebody’s Monopoly game board.”

The Impact of an Unpaid Citation

Immediate Impact

- Fine increases $300 and may go to collections

- Drivers license suspended

- Arrest warrant issued

Lingering Impact

- Harder to get housing with bad credit

- Harder to get a job without a license

- Court debt lingers even once exiting homelessness

Most homeless people do not pay their fines on time, if ever. 68% of respondents reported that they simply ignored their most recent citation. Some had tried to resolve it through the courts, but had missed their first court date, which results in an immediate bench warrant and having their initial fine added to a $300 fee sent directly to a private collection agency, which prevents any further judicial recourse. Others with serious mental disabilities were unable to decipher what even the first steps of the process would be. Many did not know that there was an option to document hours spent engaged in homeless services or community service. So once homeless respondents were handed a ticket they clearly could not pay, many decided that there was simply nothing they could do.

Others who have been homeless for longer periods and are frequently ticketed made what they saw as a rational decision: simply ignoring the ticket and just waiting until they would be brought into jail, where the courts would clear the fines after they had been incarcerated. After racking up $7,000 in fines or about 14 tickets, homeless people are brought into jail, their belongings confiscated, and are returned to the streets, usually within twenty-four hours. In short, the majority of the thousands of tickets issued to San Francisco’s homeless go unpaid.

Impacts of Citations on Homeless People

Thirty days after a citation is issued, the fine is increased by $300 and an arrest warrant is issued. After 30 more days, the fine goes to a collection agency, credit is impacted and the Department of Motor Vehicles suspends the person’s driver’s license. At this point, court personnel often claim “no jurisdiction” over the case, and refuse to reconsider it. As Assad, a 30-year-old African American man currently residing at the Navigation Center explained, “It just delays what I’m trying to do what is good for me… I haven’t got rid of them all and that’s going to delay on my situation with housing.”

The penalties described above are for a single citation, but as our study found, most homeless respondents had received multiple fines, and 25% of those who received citations had been issued over ten in the past year. The unpaid fines quickly add up to a significant barrier to gaining employment, accessing housing, and, ultimately, exiting homelessness. And when the individual finally does exit homelessness, this already harrowing experience is compounded by a legacy of debt.

A suspended driver’s license is a significant barrier to employment, not only because it disqualifies work requiring a commute or driving jobs, but because a lack of license is increasingly being used as a discriminatory signal to employers as evidence of entanglements with the criminal justice system. A recent study from Rutgers University found that 42% of people who had their licenses suspended lost their jobs as a result. Of those, 45% could not find another job. An effect was most pronounced for seniors and low-income people.

Housing is also affected by citations, as unpaid fines damage credit. This can disqualify rental applications, especially in a heated market like San Francisco’s. Arrest warrants, meanwhile, can disqualify people from receiving Section 8 vouchers, Public Housing assistance, and other City-funded housing. Getting cited for living outside can ensure that a person stays living outside.

Impacts of Citation on Homeless People

City agencies collect little data on the costs of this extensive program of punishing the poor. The City agencies contacted for this study could not provide any evidence that San Francisco’s punitive policies reduced the prevalence of any of the so-called criminal activities that such citations aim to deter. In fact officials of the Department of Public Works, the Human Services Agency, the San Francisco Police Department, and Mayor’s Office of HOPE have all publicly claimed that the current system of citations is broken and ineffective.

Not only are these policies ineffective, they are also expensive. First are the costs of enforcement: The 24 dedicated “homeless outreach” officers alone cost upwards of $2 million annually, which only includes the enforcement costs from morning until 3 p.m. each day. Even if citations take ten minutes or less to issue, such enforcement adds up to significant police and park safety patrol time each year, funneling time and money away from more serious matters. Court processing costs likely run near or over half a million a year for “quality of life” offenses.

A 2002 report to the Board of Supervisors by the San Francisco Legislative Analyst’s office on citations concluded that, “San Francisco’s current system for processing quality of life law infractions and misdemeanors indicates that the current system provides little incentive for those to pay ticket fines or appear in court and does not uniformly link defendants with social services.” Over a decade later, little has changed.

Perpetuating Homelessness through Citations

Not only does San Francisco have a larger number of anti-homeless laws than any other city in California, it enforces these laws vigorously. Since 2011, increasingly so. The result is that the majority of our survey respondents were processed through the criminal justice system in the past year due to citations, most often for performing necessary life-sustaining activities in public.

The processing of “quality of life” infractions for homeless people in San Francisco’s traffic courts is not a process of justice, but rather a farcical administrative task that neither the courts nor the homeless offenders wish to have part in.

Our research found that the citation process hardly if ever pushes people into services, but much more often creates legal barriers to obtaining housing and work.

A number of steps could be taken by the District Attorney’s office and court administration towards reducing the impact of citation on homeless San Franciscans and the cost to the City. In 2005, the District Attorney’s Office granted blanket amnesty to thousands of homeless people for their citations. Such a process of blanket amnesty could be institutionalized on a more regular basis, or some other streamlined process of dismissing these cases could be implemented. Driver’s licenses have only recently been used as debt collection tools in Traffic Court. This should be ended immediately, along with the issuance of arrest warrants.

However, a more systemic solution would be to abolish laws criminalizing homelessness in the first place. In California, Senator Carol Liu has presented legislation, Senate Bill 608, known as the Right to Rest Act, that would prohibit the enforcement of laws banning activities that homeless people have no choice but to engage in in public. While Alameda County supported the bill, San Francisco County did not come out in public support. Supervisors could be pressured to support this bill in solidarity with our East Bay neighbors while pressing for local reforms in the meantime.