In 2015, San Francisco’s Point-in-Time Homeless Count reported 6,686 sheltered and unsheltered homeless adults, as well as 853 unsheltered homeless youth, for a total of 7,539 people constituting San Francisco’s homeless population in 2015. Thirty-nine percent of the homeless population counted is white, which is a small fraction compared to San Francisco’s 53 percent overall white population, while 36 percent of the homeless population counted is Black, which is a disproportionate number compared to San Francisco’s 6 percent Black population. This means that less than 1 percent of white folks living in San Francisco are homeless, while almost 5 percent of the Black population in San Francisco is homeless. Likewise, almost half of San Francisco’s public housing lodges Black residents.

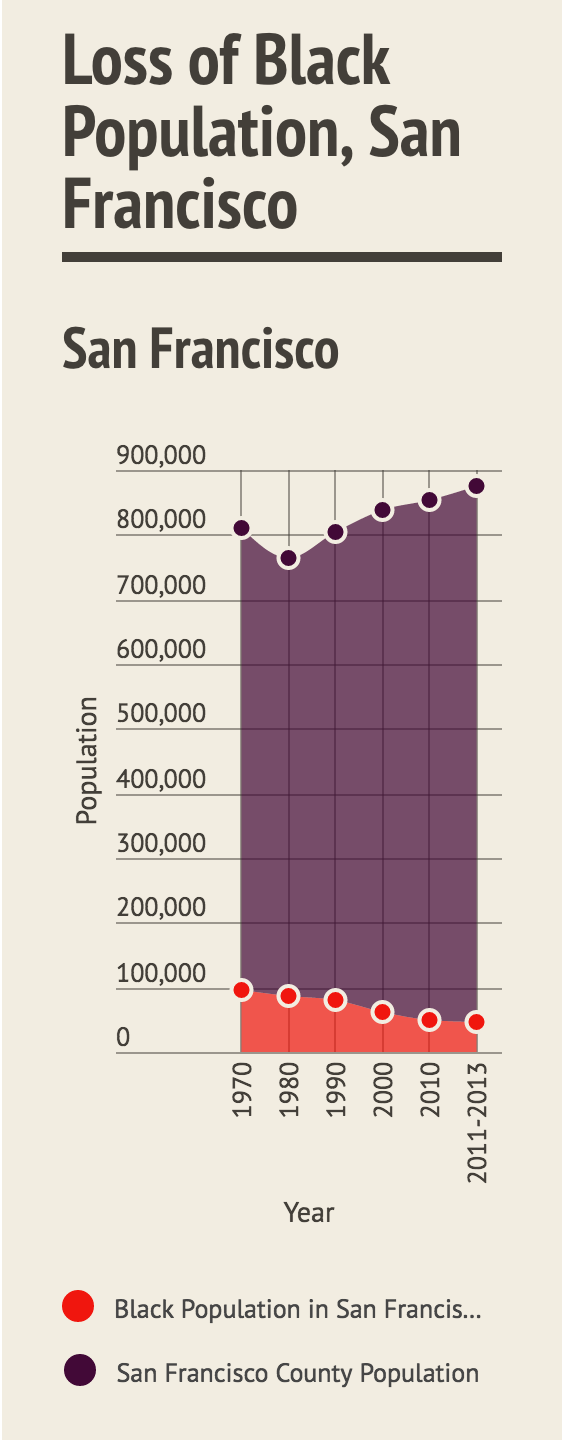

Both the smaller population of Black folks living in San Francisco in 2015 and the larger percentage of homeless and publicly houses Black folks in San Francisco in 2015 are evidence of how displacement and poverty has seriously mistreated the Black community in San Francisco. The Bay Area has been steadily losing its Black population since the 1970s. For decades, housing discrimination, underfunded public education programs, and inaccessible health care have all contributed to the disempowerment of Black folks in search of, in need of, or at risk of losing housing. These systems do not accommodate Black folks, and they directly contribute to the rising number of homeless people in the Black community and the falling number of Black residents in the SF Bay Area. That is to say, racism plays a huge role in the housing crisis and in homelessness, and the intersection of racism and homelessness is real. It is no coincidence that the Black community is overrepresented in San Francisco’s homeless population. The systems at fault are identifiable and interconnected, and I will only be able to touch on a few of them in this article.

Housing Discrimination

Housing discrimination comes in many different forms, and its objective is to unfairly limit the housing choices of America’s Black population. Some forms of housing discrimination began as public practices, while others have carried on privately, despite the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which criminalizes housing discrimination. Here I will explain redlining, blockbusting and racial steering, only three tactics of many that infringe upon the Black community’s rights to fair housing.

Redlining is a way in which businesses can impede upon the Black community’s quality of housing and is rooted in a history of racist policy and mapmaking. By redlining, businesses identify neighborhoods they don’t want to provide services to based upon the race or ethnicity of the neighborhoods’ residents, and the businesses subsequently deprive these neighborhoods of their services. According to a 2016 article by KQED, in the 1930s, a government-sponsored corporation promoted by President Franklin Roosevelt called the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), created explicitly racist maps, in which areas were rated according to the “threat of infiltration of foreign-born, Negro, or lower grade population,” for the purposes of redlining. Although policies such as the Fair Housing Act of 1968 have since been enacted to combat redlining and enforce fair housing practices, many businesses still refer to redlines to some extent today. The effects are inhumane. Cities have used this tactic to avoid investing in Black communities. Banks have also used this tactic to deny home loans to residents from Black neighborhoods. Even small businesses have maneuvered redlines by avoiding setting up shop in Black communities. This has left many Black neighborhoods without safe building structures, local employment opportunities, and even banks or grocery stores. Via redlining, businesses can not only discriminate against communities based on race and ethnicity, but moreover, they can divest these communities of safety, capital, and nourishment, amongst other necessities.

In 1970, african americans made up 13.4% of san francisco’s total population. Today, they make up little more than 6%.

Blockbusting and racial steering are other forms of housing discrimination in which neighborhood dynamics are manipulated in the interests of white homeowners and a racist agenda. Blockbusting is a process in which real estate agents and developers convince white homeowners to sell their homes for low prices by threatening the imminent influx of Black residents, and then resell the houses for profit to Black homebuyers. Similarly, racial steering is a process in which prospective homebuyers are either highly encouraged to consider or only offered houses in neighborhoods populated by people they share racial or ethnic identity with. Through these processes, real estate agents and developers were and still largely are empowered to maneuver metropolitan dynamics at the expense of Black safety and success. As with redlining, blockbusting and racial steering always resulted in secluded, affluent white neighborhoods and slighted Black neighborhoods.

It is also important to consider that home ownership itself is a form of wealth accumulation exclusive to white families and other financially privileged non-Black families of color. According to a report written in 2015 by economists Jeffrey P. Thompson and Gustavo A. Suarez of the Federal Reserve Board, assets and home ownership justified most of the wealth gap between white and Black families, with white families owning more property, having a higher net worth, and receiving more inheritance than Black families. Therefore, owning property allows white people to accumulate wealth in a way Black people are not allowed to.

Education

Housing discrimination also impacts local, public education programs, which in turn shape the communities receiving local, public education and their likelihood to secure a job, earn a living wage, and maintain housing. While a lot of funding for public schools in California is provided by the state, about 21 percent of California public school funding comes from local property taxes. However, the varying values of property across neighborhoods make this funding plan extremely unfair to students living in historically neglected neighborhoods, specifically Black neighborhoods. According to a 2016 article by NPR, while students living in wealthy neighborhoods attend highly funded schools with well-kept and multitudinous amenities, students living in poor, Black neighborhoods attend school in unsafe buildings with inadequate amenities, if any at all. Thus, Black students suffer greatly from the discriminatory business practices of racist real estate agents, bankers, small business owners, etc. who mutate the quality of life in Black neighborhoods by divesting from them. Studies have shown major racial gaps in education in which Black students being educated in a poor neighborhood are months behind their white peers being educated in a wealthy neighborhood. Consequently, Black youth are not as likely as their white counterparts to attend high school or prestigious universities. Without a high school or university education, maintaining a job and a living wage, and thus safe and secure housing, is much more difficult.

Health Care

Likewise, maintaining housing in the face of large hospital bills is also very difficult, if not often nearly impossible. Inadequate health insurance or a lack of health insurance can result in homelessness. In 2011, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) reported that Black Americans received worse health care and had less access to health care than white Americans. Without health care or adequate health care, low-income Black families confronting large hospital bills may have to decide between their healthcare bills and their rent. As an exhausting expense, health care or lack thereof can deplete a Black household of its resources to maintain housing.

Homelessness is an intersectional issue. Without regarding race and ethnicity and the unique experiences those identities encounter during and surrounding homelessness, the systems that perpetuate homelessness cannot be dismantled. Those systems have a history in discriminatory policy and business practices, and though outlawed today, they are still heavily practiced under many guises, some not so subtly.