35 years ago in 1989: San Francisco was in its first decade of mass homelessness since the Depression era.

The City opened emergency congregate shelters a few years earlier, but it would later turn away already homeless people to accommodate housed people displaced by the Loma Prieta earthquake.

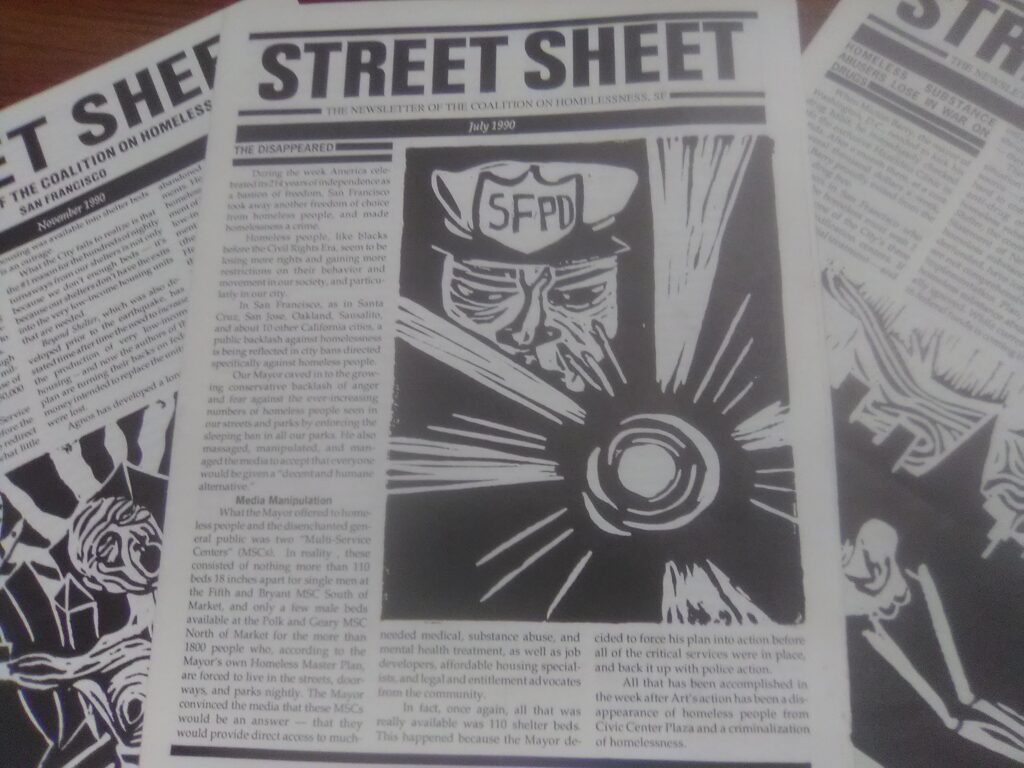

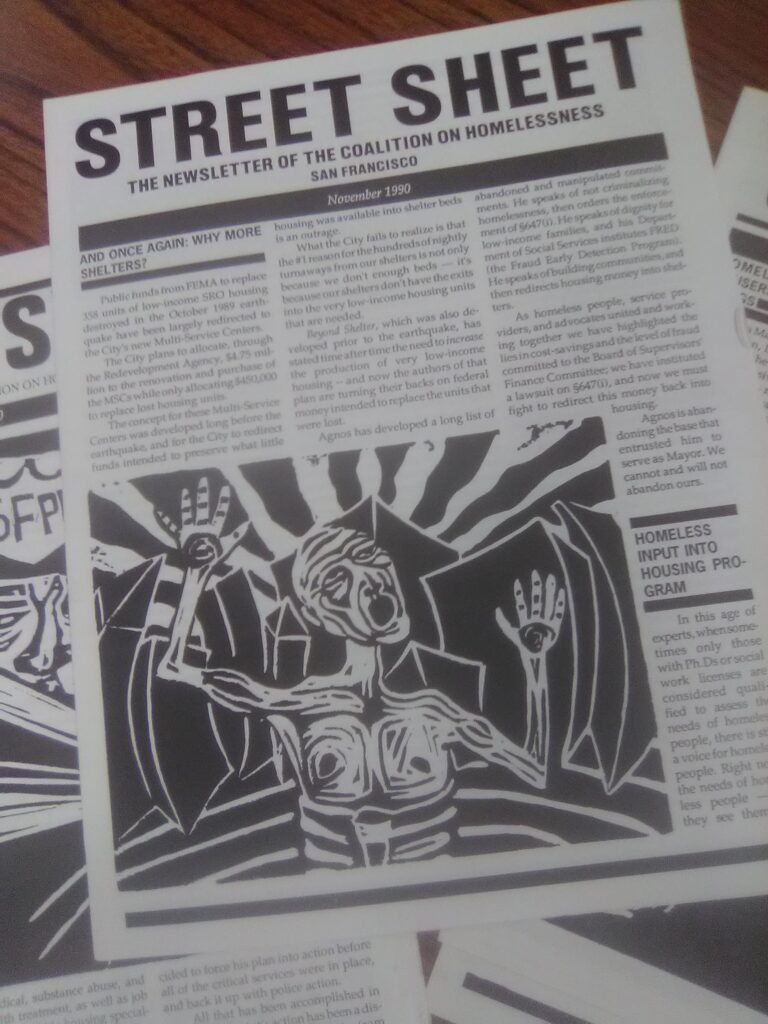

That same year, Street Sheet printed its first issue. The newsletter—originally an internal memo for members of the advocacy organization Coalition on Homelessness—was printed on 8½” x 11” paper, copied and stapled on Xerox machines.

In 1990, an excess of newsletter printed specifically for a Phil Collins concert sparked an idea to have unhoused people sell them in outdoor public areas for $1 a pop. These new vendors would now have an extra way to earn money.

Since then, Street Sheet has expanded into a tabloid newspaper. Unlike its Xeroxed forerunners, it features eye-catching, colorful artwork and bylines for its contributing writers.

The suggested donation price increased in 2014 from $1 to $2 to account for rising costs.

What people who were there at Street Sheet’s inception could tell you what hasn’t changed is its objective: Have unhoused people advocate for solutions to poverty and homelessness, and defend their human and civil rights.

“It just made sense that we would create our own voice,” Paul Boden, a Coalition co-founder who’s now executive director of the Western Regional Advocacy Project (WRAP), said. “And years later, that’s what the Coalition and [the Los Angeles Community Action Network] and others did when we created WRAP when you’re not hearing your experience with any legitimacy, and you’re being Jim Crowed by the mainstream establishment. It’s incumbent on you to create your own voice.”

Street Sheet was born at the Coalition in the Tenderloin neighborhood at 126 Hyde St. where it shared office space with the Tenderloin Housing Clinic. The paper’s first editor-in-chief was Lydia Ely, who now works as deputy director at the Mayor’s Office of Housing and Community Development, ran the paper for 10 years. She recalled the organization’s early days where the office was occupied for 24 hours daily because some staff also stayed there overnight.

“[There was] no windows,” Ely said. “Everybody smoked like a chimney, and it was pretty gnarly.”

Ely said that she observes that the challenges San Francisco’s unhoused community faced 35 years ago remain the same.

“It seems to me that these struggles, people who are homeless in San Francisco are really not changed so much about sweeps, confiscation, lack of support for mental health and behavioral health staff,” she said.

The City’s increasing wealth gap exacerbated these conditions and has also affected the political climate, Ely said.

“San Francisco is definitely less progressive than it was when I moved her,” she said. “The economics are always difficult for some people and they’ve gotten worse. The income disparities are pretty shocking.”

She noted that so-called “affordable housing” has grown out of reach for low-income people living on fixed incomes: housing for low-income people is generally built for people living on 40 to 60% of the area median income, or from $42,000 to $63,000 in today’s figures.

“And it’s not for lack of trying that we don’t build for that lower income,” she said. “But the costs of construction are so high, and the federal government, which controls the tools that were used to build affordable housing, has not crafted those programs to serve the very poorest people.”

Another constant in Street Sheet’s history is the paper’s distribution model. People come to the Coalition to pick up a bundle of newspapers to sell. Paul Wiegand, who was the paper’s first distribution coordinator and has since died, told a documentary crew in 1992 that Street Sheet would give a bundle of 50 papers to vendors 20 days out of the month. Today, vendors pick up bundles of up to 100 papers.

“It’s really a tiny, tiny band-aid,” Wiegand said. “But what tiny band-aid does is perhaps give people a break to where they don’t have to stand in St. Anthony’s line for two or three hours to get something to eat to where they could get the privacy of a low-budget hotel room for a few days out of the month to where they don’t have to live in a shelter. As small as these little things sound, it’s a real break.”

The origin of Street Sheet’s vendor distribution is a vital part of the paper’s lore. Back when the paper was a newsletter, representative of pop singer Phil Collins purportedly contacted to table at a 1990 concert in the Shoreline Amphitheatre. Collins was touring in support of his 1989 album “But Seriously,” which included “Another Day in Paradise.” The song, which hit No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 chart nine months earlier, is told from the viewpoint of a person who’s living unhoused and pleading for help.

Boden recalled that Collins had donated $10,000 to print tabloid versions of Street Sheet for concertgoers.

“We had little buckets with helium balloons and had people walking around, passing out Street Sheets and asking for donations, and we raised over $20,000 in three nights,” he said.

Still, the Coalition had thousands of papers left over.

Someone at the Coalition—no one whom Street Sheet interviewed could exactly verify whom—suggested giving surplus copies to unhoused people to sell.

“There was this poetry group that had given us a bunch of leftover poetry papers, and that’s what we first gave out to people that were panhandling, and they came back and asked for more,” Boden said. “And they were like, ‘Yeah, man, I was getting a buck apiece on these things. You got any more?’”

The rest is history.

Excerpts from Street Sheet’s earliest issues can be found in “House Keys Not Handcuffs: Homeless Organizing, Art and Politics in San Francisco and Beyond,” which Boden, artist Art Hazelwood, and homeless policy analyst Bob Prentice co-authored. Released in 2015, this compilation also includes posters and photos that the paper featured. (Editor’s note: Street Sheet has reprinted a few selections in this issue).

Joe Wilson, a Coalition co-founder and executive director of Hospitality House, said that Street Sheet’s use of artistic expression complements the paper’s advocacy and coverage of homelessness and poverty issues.

“Using music and the arts to draw attention to a deeper crisis,” he said. “You know, just behind the curtain of prosperity of capitalism and using the vehicle of a newspaper from the streets, to kind of lift up the reality of that crisis and to hopefully point people towards some more practical solutions. Among them is this idea that unhoused people still have worth and still have talent, still have gifts, and still have voices that we need to hear.”