by the Western Regional Advocacy Project

On April 22, 2024 the U.S. Supreme Court will hear the case of City of Grants Pass, Oregon v. Gloria Johnson. The case determines if the U.S. Constitution allows for local governments to fine, arrest, and jail people for living outside, when they have nowhere else to go. Western Regional Advocacy Project (WRAP) members are planning a day of action on April 22, 2024 to speak out for the rights of unhoused people to exist, in 14 cities and counting!

The Case: The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which governs nine states in the western U.S. including Oregon, has ruled that criminalizing basic survival amounts to cruel and unusual punishment. But Grants Pass is challenging that ruling. Grants Pass officials have explicitly stated their goal is to make the city “uncomfortable enough for [unhoused people]” that they decide to “move on down the road.”

Currently, cities are not supposed to criminalize sleeping if no “shelter” is available. Temporary shelters are no replacement for housing. Yet, the current legal requirement that cities cannot criminalize people if there are no shelter beds available gives unhoused people some legal recourse in court when they are cited and arrested for basic survival activities, such as sleeping, sitting, standing and eating.

What’s At Stake: Over the last 40 years, thousands of lawsuits have been filed to protect the rights of unhoused people in public spaces. But the Grants Pass case would remove current meager protections—which already allow for incredible violence to occur.

A typical sweep goes something like this one, experienced by WRAP members in Denver: on January 5, 2024 around 10 a.m., several police officers arrived at a 30-person encampment on the corner of Colfax and Mariposa Streets. Tents were on the public right-of-way, not blocking the sidewalk. It was 32 degrees with a wind chill of 27; below-freezing temperatures persisted nearly the entire month. Officers told residents they had 72 hours to pack up and leave. Twenty minutes later, however, city workers began throwing tents, backpacks and other belongings into garbage trucks. Residents asked for time to pack their belongings, but crew members ignored them, trashing personal items: food, essential paperwork, sleeping bags, clothing, work tools, medication and identification.

Though methods vary, forced displacement is always traumatic. If Grants Pass wins, it will be even easier than in the past for police to roll up to encampments at the behest of elected officials, and send people to jail for refusing to leave their tent, vehicle or community. It would allow governments more leeway to disappear people carte blanche. Unsheltered people would continue to be pushed from block to block, from city to city, each time becoming more targeted, more degraded and more dehumanized. Cities would do this with violence and impunity, with less fear of potential litigation.

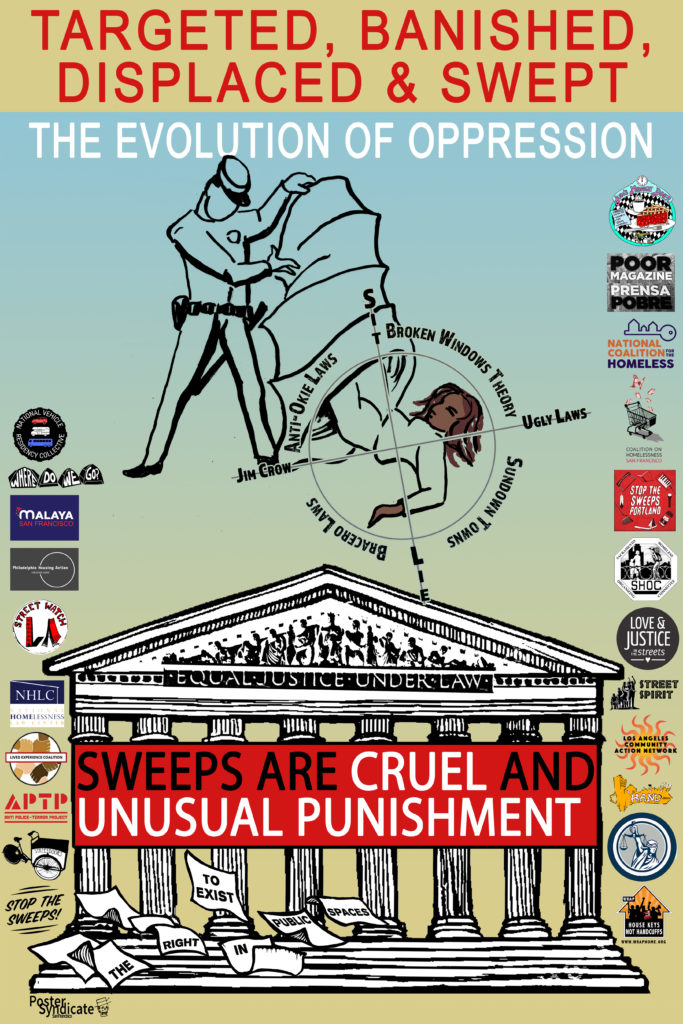

This is the same kind of power and property grab that those in power have been trying to get away with for centuries.

History of Banishment: Governments have been using laws to control the use of public space by particular community members since the birth of this nation. The criminalization of poverty and homelessness has ALWAYS existed to ease racist fears and protect (predominantly white people’s) property and profits. Unhoused people, and especially indigenous communities, Black and brown people, trans and queer folks, immigrants, and people with disabilities, are hit hardest—but now we’re rising up.

White settler efforts to control public space began with the genocidal theft of indigenous lands. Early colonizers then brought anti-poor laws banning “vagrancy” across the Atlantic, enacting “warning-out” laws that enabled towns to force unemployed individuals out of the area. Warning-out laws ostensibly protected towns from “economic instability” brought on by newcomer residents lacking gainful employment, and provided a legal mechanism for authorities to control public space.

In 1619, white plantation owners established the horrific institution of slavery, controlling nearly every aspect of the lives of Black people. Following the formal abolition of slavery, vagrancy laws were repurposed to control Black folks. Local Black codes, passed in nearly every Southern state, established brutal punishments for unemployment. Tens of thousands of Black people were arrested and fined, and failure to pay fines resulted in forced labor. Southern states went on to banish Black individuals from public space using Jim Crow laws. Simultaneously, cities across the country adopted “sundown town” policies, prohibiting the presence of Black, Chinese and Latinx people in public after dark. The City of Grants Pass itself was a sundown town, and leaders explicitly targeted the act of sleeping for non-white people.

The ugly laws likewise aimed to control the presence of disabled people. Chicago’s 1881 ordinance read: “Any person who is diseased, maimed, mutilated, or in any way deformed, so as to be an unsightly or disgusting object, or an improper person to be allowed in or on the streets, highways, thoroughfares, or public places in this city, shall not therein or thereon expose himself to public view, under the penalty of a fine of $1 [about $20 today] for each offense.”

In the 20th century, other instances of displacement came via anti-Okie laws. During the Great Depression and Dust Bowl, hundreds of thousands of displaced farmers, referred to derogatorily as “Okies,” migrated to western states. Local governments passed laws to punish the presence of displaced farmers who lived in “shanty towns.” For example, a Yuba County ordinance said “[e]very person [or entity] that brings or assists in bringing into the State any indigent person who is not a resident of the State … is guilty of a misdemeanor.”

Banishment Today: Laws banning camping like the one in Grants Pass are the 21st century’s version of this trend. When elected officials in Grants Pass first enacted the anti-camping ordinance that became the basis for this Supreme Court case, they made it crystal clear that their goal was to banish unhoused people from the city.

When a group of people threatens the very root of the system that keeps the powerful empowered, governments move to legislate against them. The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 required that slaves be returned to their owners even if they were in a free state, for example. These days, substantial profits come via real estate, retail and tourism. When the presence of unhoused people threatens profits, elected officials call the police. Police cite, fine, arrest, jail, harass and displace people surviving unhoused. Instead of providing public housing, tenant protections and other support, officials banish those who cannot afford housing.

The actions of local governments imply that homelessness is only a problem if you can see it. These centuries-old efforts to make us disappear can be collectively described as “invisible laws”: if you can’t see homeless people in your community, then you have eliminated the issue of homelessness in society. We know this is not true.

Fighting Back: These fights we engage in are not just about winning or losing, they are about building community. They are about letting poor and unhoused people know, in no uncertain terms, that we get stronger when we join forces and defend our rights to exist in the places we call home.

When poor people see our reality respected and celebrated in the public domain, we build power. In this power, one day the change we organize for will come. Dignity, respect, celebration, accountability, and love are the building blocks of our community organizing. Come out with us on April 22 to bring attention to the Grants Pass case, have a blast, and of course, kick some ass!