by Dilara Yarbrough

This is the fifth article in a series covering the criminalization of homelessness in San Francisco drawing from findings of the Coalition on Homelessness’ recently released report Punishing the Poorest, based on the COH’s survey of 351 homeless San Franciscans, and in-depth interviews with an additional 43 participants. You can download the report watch a video based on the interviews online at the Coalition on Homelessness’ Website.

In July, a video showing San Francisco police officers beating a disabled Black homeless man brought renewed attention to police violence against homeless people, especially people with disabilities. (A video of the incident is on-line at Medium.) Already under scrutiny following the discovery of racist and homophobic text messages sent by a number of officers, police officials have apologized and pledged to root out misconduct in the department.

While it is crucial to address the prejudice and biases of individual officers, the problem is not just with a few bad apples. Even if the department were to fire all officers who expressed racist beliefs and used excessive force, it is likely that we’d still see that the enforcement of quality of life laws perpetuates racial inequalities. This edition’s article, the fifth in the Coalition on Homelessness’ Punishing the Poorest series, explores how the criminalization of homelessness deepens racial and gender inequalities. The criminalization of homelessness affected most of the 351 currently and recently homeless people we surveyed, regardless of race or gender. At the same time, our study results indicate that the criminalization of homelessness perpetuates racial inequality and heightens vulnerability to gender-based violence.

Race and the Criminalization of Homelessness

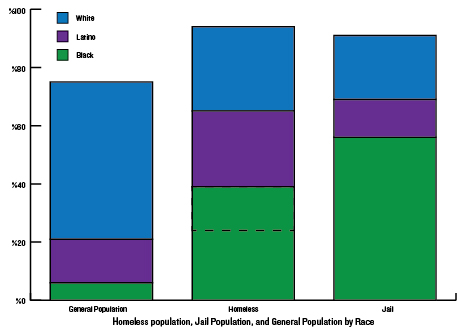

San Francisco is becoming increasingly white, and people of color are being priced out and pushed out of the city. Black and Latino San Franciscans who remain are more likely to live in poverty than white San Franciscans. As the local Area Median Income soars, extreme poverty deepens. Black people are 6% of San Francisco’s population, but 24% of homeless people counted in the city’s last point-in-time survey, and 56% of people incarcerated in San Francisco jail. San Francisco’s Black population has decreased by 50% since 1970, a faster rate than that of any other US city. This is due in large part to redevelopment policies enacted in the ‘60s and ‘70s to drive Black people out of their homes, and contemporary “developer-driven” policies that prioritize profit over the preservation of affordable housing.

| Black N=129 | Other Person of Color N = 105 | White N = 112 | Asian N = 18 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Approached | 81% | 84% | 77% | 69% |

| Forced to Move | 67% | 75% | 72% | 69% |

| Cited | 76% | 70% | 66% | 77% |

| Searched | 62% | 55% | 52% | 54% |

| Property Taken | 40% | 42% | 36% | 50% |

| Incarcerated | 74% | 53% | 51% | 54% |

| Probation or Parole | 24% | 20% | 17% | 14% |

Racial categories are not mutually exclusive; participants could select all that applied.

Like Black San Franciscans, Latinos are over-represented in the homeless population. Latinos are 15% of the city’s population, 26% of homeless people counted in the city’s last point in time count, and 13 percent of the San Francisco jail population. In contrast, whites are 54% of the general population of San Francisco, 22% of the jail population, and 29% of homeless people counted in the last point-in-time survey.

Not only are Black people and Latinos disproportionately represented in the homeless population, they also experienced police interactions, citation, arrest, and incarceration at the highest rates of all our homeless respondents. Black survey participants were more likely to be cited, arrested and incarcerated than survey participants of any other racial group. The overwhelming majority of Black survey participants were approached by police (81%), searched (62%), forced to move (67%), cited (76%) and arrested and incarcerated (74%). Replication of this study would likely again demonstrate that across the board, 1) homeless respondents are much more likely to be arrested than people who are housed, and, 2) Black men and Black transgender women experience the highest rates of arrest and incarceration.

Of all the different categories of disadvantage reviewed, race was most closely tied to frequency of law enforcement interactions, especially incarceration.

As Joseph, a 68-year-old Black man interviewed for the study explained:

“Asians, Blacks, Latinos and Chicanos—I feel [police] target them the most… I want to think it’s something like a written thing, that if you are any of the people I just named, then you are doing something wrong for that matter. They automatically come up with that mindset, thinking, ‘You can’t be doing anything right, you got to be doing something wrong. There’s too many of you together, so there’s got to be something going on that’s not right.’”

A national survey by the Western Regional Advocacy Project (WRAP) found that homeless people widely perceived their race, gender, and disabilities as factors in being given citations; 77% reported that they believed they were ticketed because of their economic status, but 35% reported it was also or solely because of their race, 24% their gender, and 24% their disability.

Mass incarceration not only deepens poverty, it also perpetuates racial inequality: Nationwide, 11% of 25–29-year-old Black men are incarcerated on any given day, and one-third of Black men in their twenties are under correctional supervision. Black men are over six times more likely to be incarcerated than white men, and Latino men are 2.5 times more likely to be incarcerated than white men.

San Francisco is no exception to the national trend of mass incarceration of poor people of color: 56% of people incarcerated in the San Francisco jails are Black, and 84% of people in San Francisco jails have not been convicted of any crime—they are in jail simply because they are unable to afford bail.

The most dramatic disparities in rates of arrest and incarceration in our sample are between Black and white survey participants: 77% of Black men (N=97) and 57% of white men (N=78) who participated in our survey had been arrested and incarcerated at some point in their lives.

The disproportionate incarceration of Black people in San Francisco is so taken for granted that the Controller’s Office assumes a reciprocal relationship between San Francisco’s Black population and the City’s jail population. In a breathtaking normalization of systemic racism, the San Francisco Controller’s Office uncritically states that the more Black San Franciscans there are, the more Black San Franciscans will be in jail:

“The African American population in San Francisco decreased by 18 percent (59,461 to 48,870) between 2000 and 2010, and the DOF projects a continued decline through 2050 to 34,101. These population changes are relevant because, as mentioned previously, adults age 18 to 35 and African Americans are disproportionately represented in the jail population. A decline in these populations could have a downward impact on the jail population into the future.”

This statement acknowledges San Francisco’s policy of massive incarceration of Black San Franciscans—and then normalizes it. Rather than questioning racist policies that result in the hugely disproportionate number of Black people behind bars in San Francisco, City officials take for granted that a large proportion of the city’s Black residents have always been, and will always be, in jail. Officials assume that Black San Franciscans will either be locked up or priced out of the city.

It is likely that such assumptions—by police officers as well as court personnel and elected officials—both demonstrate and result in anti-Black discrimination.

Trans People and the Criminalization of Homelessness

Nationally, transgender people and especially transgender women of color, experience homelessness at higher rates than other groups. Trans people are an estimated four times more likely to have a household income below $10,000 than the general population. 19% of participants in a national survey of 6,450 transgender people said they became homeless as a result of anti-transgender bias or discrimination and eleven percent reported that they had been evicted due to their gender identity.

One out of five transgender Californians in a separate survey experienced homelessness after they first identified as transgender. The rate of homelessness among trans people is estimated to be over 2.5 times higher than the lifetime rate of homelessness in the general population (7.4%).

Black transgender and gender non-conforming people reported that they were currently homeless at the highest rate (13%), compared to other racial groups. Many gender non-conforming people also reported being marginally housed: 26% of all trans respondents, and 48% of Black trans respondents in the national survey had experienced housing instability during the past year. The disproportionate incidence of homelessness in the trans population is due to pervasive housing and employment discrimination, and family rejection.

With nowhere to go and a high likelihood of encountering anti-trans harassment or violence, trans people who end up on the street are likely to interact with police in public space. 16% of respondents to the National Transgender Discrimination Survey (a national survey of trans people throughout the US) spent time in jail or prison “for any reason,” and 7% of transgender respondents had been arrested and incarcerated “strictly due to bias of police officers on the basis of gender identity/expression.” 47% of Black trans respondents and 30% of Native American respondents reported past incarceration, along with 21% of all trans women and 10% of trans men who participated in the survey. These rates of incarceration greatly exceed those of other demographic groups.

Trans people are often mis-gendered in jails and prisons, so there is no official source of data on the number of transgender people who are incarcerated. However, the results of this national survey indicate that transgender people are particularly vulnerable to getting caught in a cycle of homelessness and incarceration.

Trans participants in the COH’s study reported frequent and negative interactions with police.

Sindi, a 57-year-old white transgender woman explained: “Cops harass me. I think it’s none of their business, but they want to pull up and harass me, because I’m transgender… Being poor, they treat you with no respect at all, because they think you have no human rights at all. I had more contact with cops after I became homeless.”

Beti, a 75-year-old transgender man said: “Being gay and identifying as trans affects me greatly. When I interact with the police… they don’t treat me as much as a second class citizen, as not a citizen at all… an alien.”

Many gender non-conforming people told COH surveyors that they felt more vulnerable sleeping outdoors after being forced to move from a familiar location. Gender non-conforming people most frequently reported feeling “less safe” after City officials forced them to move to a new location. Whereas 30% of survey participants overall reported feeling less safe after being forced to move, 59% of gender non-conforming participants felt less safe after they were forced to move.

Sindi explained: “You could sleep with one eye open and be safe. But there’s some of us who can’t sleep like that… Night is when the predators come out.”

Transgender participants told us that they felt law enforcement targeted them due to their gender identity, their status as homeless or marginally housed, and—for transgender women of color—their race.

Of 10 Black transgender women participants in the COH study:

- Nine were approached by police.

- Seven had been cited by the police.

- Six were forced to move.

- Four had their belongings taken away and destroyed.

- Seven had been arrested and incarcerated.

Of 10 respondents who identified as trans men or genderqueer:

- Eight had been approached by police.

- Seven had been searched.

- Three had been cited, and three had been arrested and incarcerated.

The complacency of many City officials in the face of policies that produce disproportionate rates of both homelessness and incarceration among Black and transgender San Franciscans helps to explain the extremely high numbers of Black and transgender homeless respondents to our survey who have been arrested and incarcerated, and who have found themselves homeless upon release from the SF jail.

Race and gender inequalities can happen even in the absence of personal bias or prejudice, but this doesn’t mean that these inequalities are inevitable.

Regardless of policymakers’ intentions, San Francisco’s investments in the enforcement of anti-homeless ordinances and jail expansion deepen racial and gender inequality. By investing in housing rather than policing and jail expansion, San Francisco could promote racial and gender justice.

Stay tuned for next issue’s installment, which will discuss the devastating impacts of criminalization for homeless people with mental illnesses.