In 2008, the Salvation Army opened a community center at 242 Turk St. in San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood. It’s a Ray & Joan Kroc Community Center, whose stated mission is to provide supportive health services and housing for formerly homeless adults, foster youth and veterans living with behavioral health conditions, and nurture a safe space for the community’s youth. Next to the center is Railton Place, an apartment complex owned by the Salvation Army and managed by the John Stewart Company, which houses nearly 200 residents.

Little did the residents or the Tenderloin community know that the Salvation Army would essentially occupy and take over every community space in the Kroc Center’s residential and recreation sides, including those areas designated specifically for residents’ use.

The Salvation Army has been using its community space to store jeans and furniture for its stores.

This takeover happened at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, when the center closed down community rooms in multiple floors of the building. But those rooms remain closed to members—even after the state and City lifted their health emergency orders last year.

Since the rooms have been locked off during daytime, evening and night hours, it has been altogether impossible for residents to spend time together in these rooms. Residents say that it has interfered with their enjoyment of the living spaces and their ability to have a place to meet with invited family and friends or engage in other activities like eating lunch, reading a book, or otherwise increase the quality of their lives.

Even the front desk area lends the appearance of a place in lockdown: A metal perforated gate encircles the desk. A bench that was once there has been long since removed.

Residents feel that by locking them out of their beloved community rooms and interfering with their use for resident meetings, management has violated terms of the lease.

Residents also say that their overall wellbeing has drastically declined because of constant trauma and abuses from staff. They say they’re being harmed emotionally and physically by Salvation Army workers. They maintain that it’s difficult to hang out with friends, family and neighbors without security hovering over them.

If so, the Salvation Army is dedicating more resources befitting a carceral setting than permanent supportive housing—like a prison treatment center minus the housing services.

But even those who are incarcerated have access to recreational facilities. At the Kroc Center, access doorways in the main lobby to the gym and recreation restrooms are locked. Residents are unable to use their key fobs to enter the two front doors and are restricted from passing through connecting doors to the gyms, the rec center and the swimming pool. If residents do manage to get through, they are immediately swarmed by front desk staff, who remove them from the area immediately.

Maintenance at the building has also been a vexing issue. The pool at the Kroc Center was the only one available to neighborhood residents until the Salvation Army closed it due to a crack that was never fixed properly. The Department of Building Inspection noted building code violations in the last year such as broken light fixtures and exposed electrical wiring. As for the community rooms, Salvation Army directors dispute that they are community spaces; they claim those are meant for staff programs and private organization-related activities.

Independent access to the building’s courtyard has also been a source of frustration for residents. The adjoining doors used to be unlocked and open up to four hours per day to adult residents when the courtyard was not used for youth programs. Now, they must sign release forms before being allowed to walk out in the yard to socialize or attend any organizational program—all under the watchful eyes of Salvation Army staff.

The ongoing residential community lockout has also been extended to the basement parking area. Once used as a shared space between the Salvation Army and the residents, the former disabled parking space is now used as a dumping ground for discarded household items and repurposed furniture.

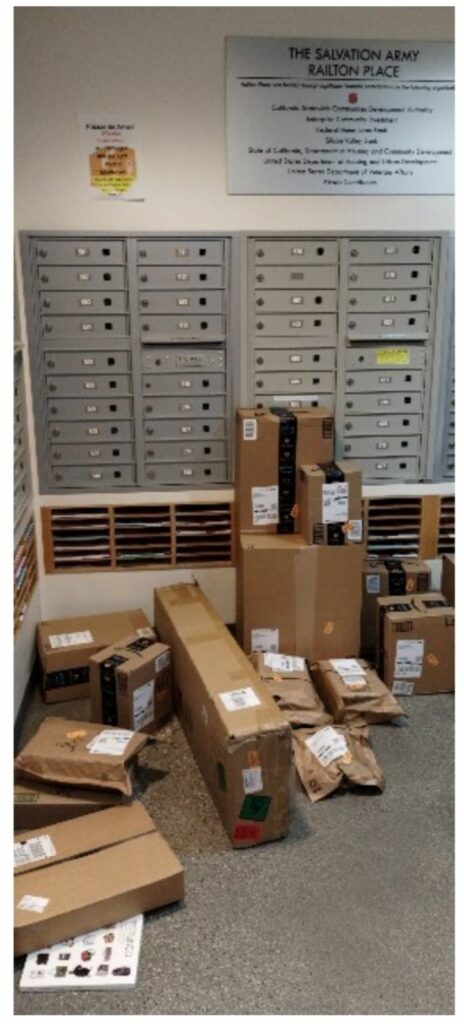

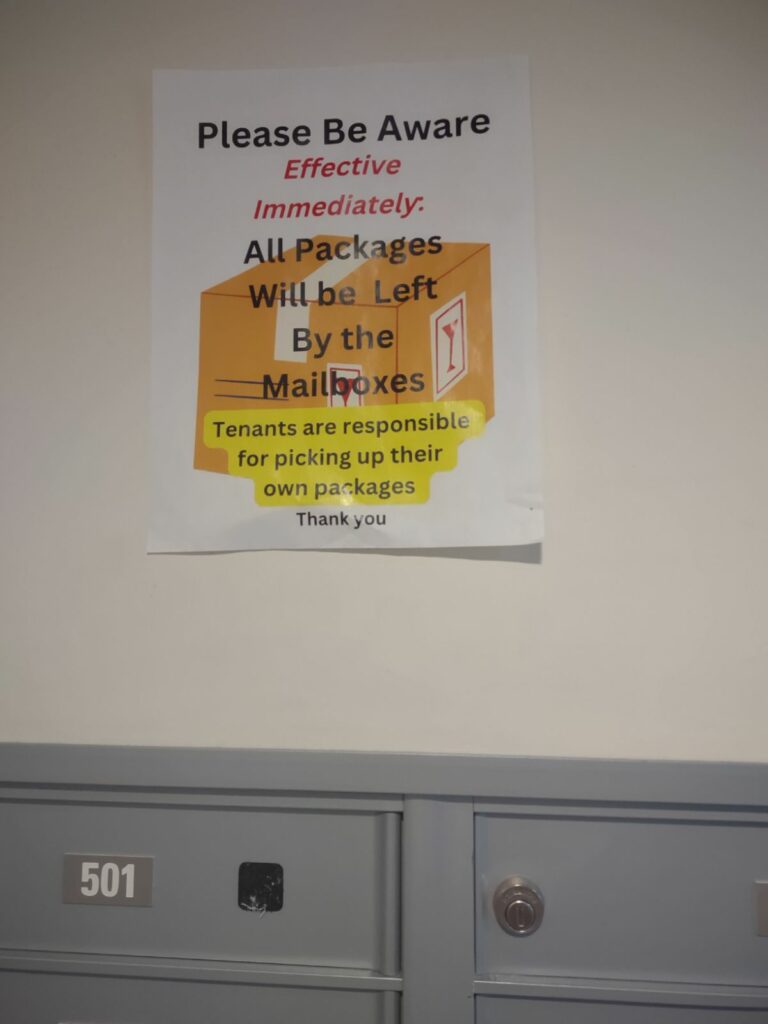

The lobby has also become a junk pile. Next to a set of mailboxes, packages delivered to Railton residents lie damaged and opened because management has ceased storing them in a safe and secure area. “Please be aware effective immediately all packages will be left by the mailboxes,” a sign above the mailboxes reads. “Tenants are responsible for picking up their own packages.”

On the third floor, residents and guests were once free to use the community room with its coffee station and relax. Now, it has been commandeered for management offices, replete with cubicles. To enter that space now, residents must ring a doorbell and navigate a series of locked doors—all just to set up an appointment with a case manager.

But most shocking among all the spaces now closed to residents is the removal of the social service office in the lobby. That was where social workers met with residents. It is now a coat closet and break room for front desk staff.

Resident Tenant Union Formation

In response to all the trauma and problems with community lockouts from the Salvation Army and John Stewart Co., Railton Place residents formed a tenant council last November to help improve the quality of life for all residents and to prevent tenant displacement from permanent housing. However, the Salvation Army declined to allow the union to access a meeting room in the residential building community space and instead encouraged the tenant union to find one at another building. The Railton Place tenant union meets monthly online and has been trying to get help from outside organizations like San Francisco Housing Rights Committee, San Francisco Tenants Union, Herbst Foundation, and Neighborhood Tenants Council to help urge Salvation Army to reopen the community residential rooms on each floor and restore residential access to the community areas in the building.

Tenants are left wondering if these same horrible community closures, evictions and unending trauma are widespread in Kroc Community Centers across the nation. How many other residential housing areas are experiencing community lockouts similar to the Tenderloin by the Salvation Army and affiliated management companies? What will it take to replace the Salvation Army with a more responsible and competent organization—such as the San Francisco Recreation and Park Department—to operate the Kroc Community Center in a way that provides meaningful community services to help keep homeless adults and youth off the streets, retain permanent housing for residents, and maintain community recreation services for members living onsite and within the greater Tenderloin community?

At the author’s request, Street Sheet is running this story without a byline.