Time and space work together to both reveal and obscure communities and cultures at work. Today, our world-class art museums sit at the intersection of the Financial District, the Tenderloin, the city’s most dense retail area, and the Filipino Cultural Heritage District. Each community and neighborhood is populated by individuals with diverse values, beliefs, and histories. Often, they are seen to outsiders as a monolith or singular entity with a unified voice. Entering into each space, spending time working in solidarity with each community, a rich history is revealed—one of revolutionary voices rising up for equity and justice. This work continues to take place on Ohlone land.

As residential zones, the Tenderloin and the Filipino Cultural District of SOMA could hardly be more distinct, but the biggest differences may not be obvious. Although residents of both neighborhoods have been impacted with dire consequences, the Tenderloin has powerful zoning laws that have served to protect more of its historic buildings from the massive waves of gentrification and displacement that have impacted SOMA. The Filipino Cultural District has not been so fortunate and has been fighting for its survival for over 40 years. This August, The Manilatown Heritage Foundation has been commemorating the historic fight for the I-Hotel, during which more than 3000 protesters surrounded the building to prevent the eviction 197 residents, slated to be torn down to make way for ‘urban renewal.’ (The new I-Hotel reopened in 2005). Many smaller communities are gone altogether, as SOMA once included a strong veterans community, a thriving queer leather culture, and a network of spaces for single elders.

What role do the arts play in gentrification and displacement? We share the perspectives of Kearny Street Workshop (KSW), an organization that uses art as a way to present, produce, and promote the work of the Asian Pacific American community, Hospitality House, which uses art as a revolutionary tool to fight for justice, Bay Area artist and anti-eviction organizer Leslie Dreyer, and culture workers from LATU/SILA, who call on the arts community to stand in solidarity with neighborhoods being impacted and erased by the housing crisis. Lastly, we issue a call-to-action for institutions already involved in the conversation, to take a stand and make a commitment to equity and justice in their own work, both internally and in the community, and to examine the role of their programs and funds on gentrification and displacement in San Francisco.

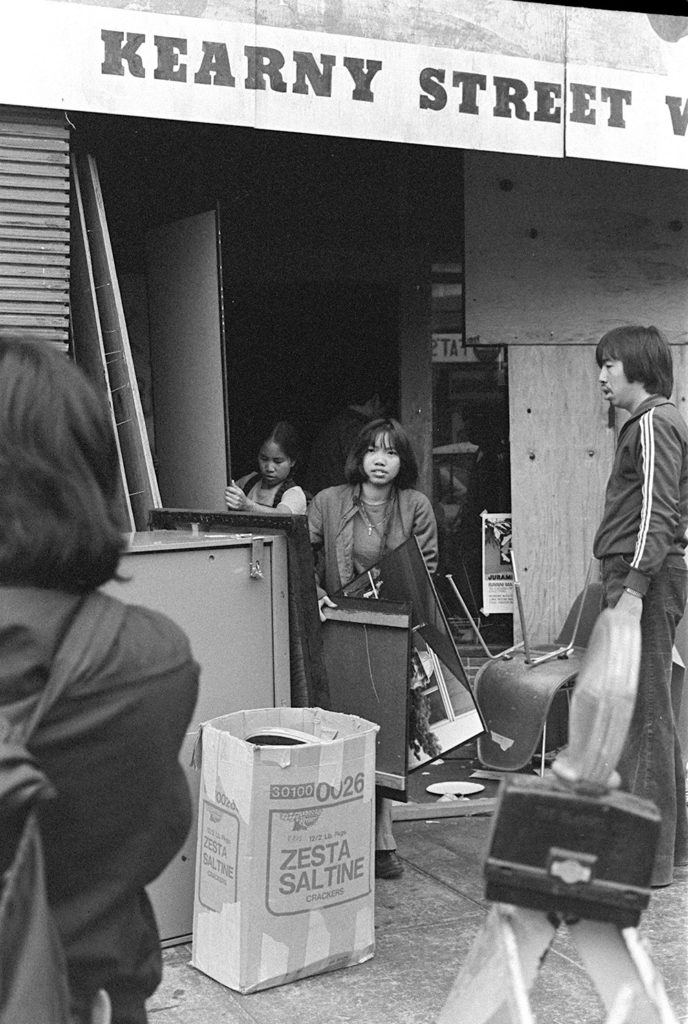

Kearny Street Workshop at 45

What does it take for an arts organization to survive a major eviction? How can an arts community continue to thrive through precarious economic cycles and waves of displacement and gentrification? Kearny Street Workshop, now in its 45th year, may be the most powerful model we have.

Begun in 1972 in the I-Hotel, KSW in its many iterations has included a small press, gallery exhibitions, a jazz festival, writing classes, and more. Caught in the eviction of 1977, KSW was displaced along with two newspapers, a bookstore, and a gallery. As the nation’s oldest multidisciplinary arts organization created by and for the Asian Pacific American community, KSW continues to serve the needs of artists in the Bay Area. The secret to their longevity? “KSW makes artists out of community members and community members out of artists.”

Today KSW shares space with ARC Studios in SOMA, but their educational and performance offerings can be found throughout the city. This summer, in conjunction with the Asian Art Museum, KSW launched the Interdisciplinary Writers Lab, a three-month, master class for local writers of color. Fifteen up-and-coming authors are developing major new works to be published in a culminating anthology. APAture Arts Festival will celebrate its 15th anniversary this fall. The ground-breaking series features emerging voices alongside established artists showcasing work across genres.

“For fourteen seasons, the festival has sparked dialogue around contemporary social issues, especially those that affect Asian and/or Pacific Islander communities, and inspired collaboration between artists and community members toward social action.” This year’s theme is “unravel,” asking what can be seen when the threads that connect us are untangled and examined? With an organizational legacy rooted in a tightly woven network of people, institutions, neighborhoods, and communities, KSW reflects the power of the ties that bind us.

For more info, contact Director Jason Bayani at jason@kearnystreet.org.

This is Our City Too!

Artwork by Hospitality House’s artists, Devan Saundry.

On August 18th, the Community Art Center at Hospitality House will debut This Is Our City Too!, a group show reflecting on the changing city of San Francisco. Recognizing that this has always been a city of change, artists ask, “At what cost is this current variation? How many more long-time residents, artists and diverse neighborhoods do we have to lose to displacement and gentrification? How many more families need to become homeless before we see more affordable housing?” This exhibition serves to lay claim that in spite of the winds of change, we’re still here and This is Our City Too!

Hospitality House was founded in 1967, when the Tenderloin was experiencing an influx of LGBT youth flocking to the epicenter of the queer liberation movement. Despite the positive legacy it created, more than 3,000 of these youth found themselves living on the streets. Concerned residents in the Tenderloin partnered with the young people to form Hospitality House. By 1985, Hospitality House had developed into the multiple-program agency it is today. The demographic focus has shifted to meet changing needs of the community and now serves predominantly adult residents of the Sixth Street Corridor and Mid-Market neighborhoods struggling with homelessness, poverty, and other socioeconomic issues. Its programs include two Self-Help Centers, a Community Building Program, an Employment Resource Center, a Shelter and the Community Art Program.

Since 1969, the Community Arts Program has provided a free-of-charge fine arts studio for local artists who lack access to creative resources. Instruction, exhibition and sales opportunities are available while providing low-threshold, peer-based support in a safe space for artists to create, inspire and collaborate with one another. Every 6 weeks, work made in the studio is shared with the public and 100 percent of sales go to the artists.

For more info, contact Program Manager Janet Williams at jwilliams@hospitalityhouse.org.

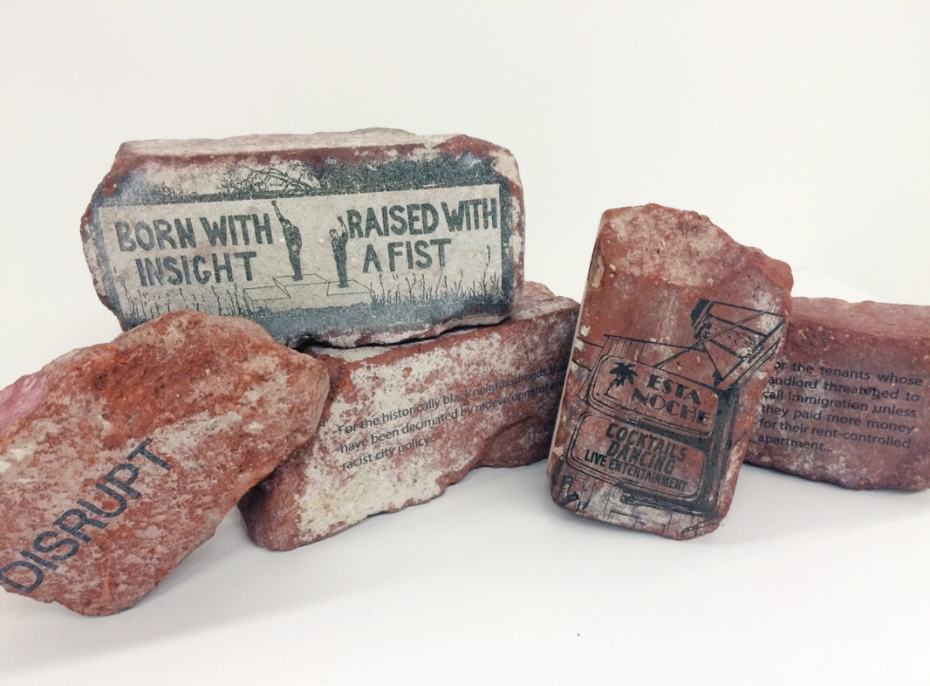

Art Against Displacement

Developers and speculators use the arts to rebrand neighborhoods and even whole cities as “creative” to lure capital and those accumulating it, which dramatically drives up rents and drives out low or no-income residents. Thus, an artist’s role in gentrification and displacement needs to become one of active resistance to it.

When San Francisco cultural institutions use developer dollars to produce public art and ‘community prototyping’ or ‘placemaking events, they risk replacing everyday, non-curated public communing and increasing the policing of our common spaces. This additional control sets a new standard where neighbors who once played chess, music, or sold art without institutional sanctioning now have to get permission to use their own sidewalks. Since SF has more laws criminalizing homelessness than anywhere else in California, those in the Arts should do ample outreach to residents (with and without shelter) before trying to remake an existing place, and fight the increased police presence that may accompany their initiatives.

Cities are becoming whiter, more affluent and as author Jeff Chang notes, “resegregated,” yet most art institutions and artists supported by them aren’t willing to have raw conversations about race, class and equity. They’re still talking about ‘activating public space’ rather than actively resisting and refusing to benefit from our capitalist, white supremacist systems. Now more than ever, we need artists and cultural orgs to go beyond representing politics and dissent and ask how they can use their skills and access to halt the hemorrhaging of, violence against, and exploitation of our vulnerable populations.

The most effective cultural organizing work comes from within social movements and grassroots efforts led by marginalized communities. These are the “center[s] for the art of doing something about it.”[1] I urge artists to join these fights for racial and economic justice and use their skills to help pursue rights to a roof and the city for black, brown, LGBTQ, disabled, low-income, and homeless residents who all need sanctuary

[1] YBCA advertising campaign language

Leslie Dreyer is Bay Area artist and anti-eviction organizer.

Well then do something about it!

From 2016-2017, Yerba Buena Center of the Arts (YBCA) convened a 30-person fellowship to address the question, “What does equity look like?” What quickly became apparent was that YBCA’s lack of equity lens, institutionalized within their culture, was a major barrier for the fellows to be able to move forward. With no formal structure with which to investigate the question together, the cohort worked through the challenges of developing individual and group projects in response. One such project asked YBCA to create an equity framework and provided an example, developed through community relationships with the San Francisco Human Rights Commission, Race Forward, and Animating Democracy. YBCA responded that they were unwilling to share a formal commitment to adopting an equity framework, now or in the future. We provide the equity framework here in hopes that you, the reader, will support YBCA in adopting these principles to examine the relationship between their programs, the community in which they reside, and the potential impact of their programming on gentrification and displacement.

+ We examine the policies, practices and procedures that create and contribute to the health, safety, economic welfare and environment of a community, including collecting data on structures, relationships, resources, and other determinants of equity. In the development of each project, we will ask:

How have the artists and stakeholders explored the relationships of power, privilege, and cultural context within the process of making the work?

How have the artists and stakeholders explored questions of credibility, authenticity, and integrity?

How does the work reflect an enduring commitment to the community, practice, situation, locale, or issue/topic?

How do the people affected by the work have agency to act on their own behalf?

Is the work factually accurate where such accuracy is called for?

Have the artists and stakeholders considered what they might be taking away and what they can leave behind that is meaningful in a cultural context?

+ We build relationships with community that yield mutual benefit, recognizing the ways in which previous policies, practices, and investments have been insufficient in achieving equity. With community, we will examine the potential of programming to result in unintended outcomes, including gentrification and displacement.

+ We create opportunities to move people and ideas from the community upward through channels of power they have often been prevented from accessing, honoring the fact that community members have specialized knowledge on the way in which policies, practices, and investments have benefited and burdened their neighborhoods.

+ We cultivate collaboration to ensure that policies, practices, and investments that have not ended or otherwise reduced disparities are not replicated.

+We visualize equity successes and plan for how impacts will inform future work, aiming for transformational rather than transactional programs and projects.

This article of the Street Sheet was created by artists from SF and LA in collaboration with members of the Equity Cohort and partners at organizations and agencies across the Bay Area.